SLAUGHTERHOUSE

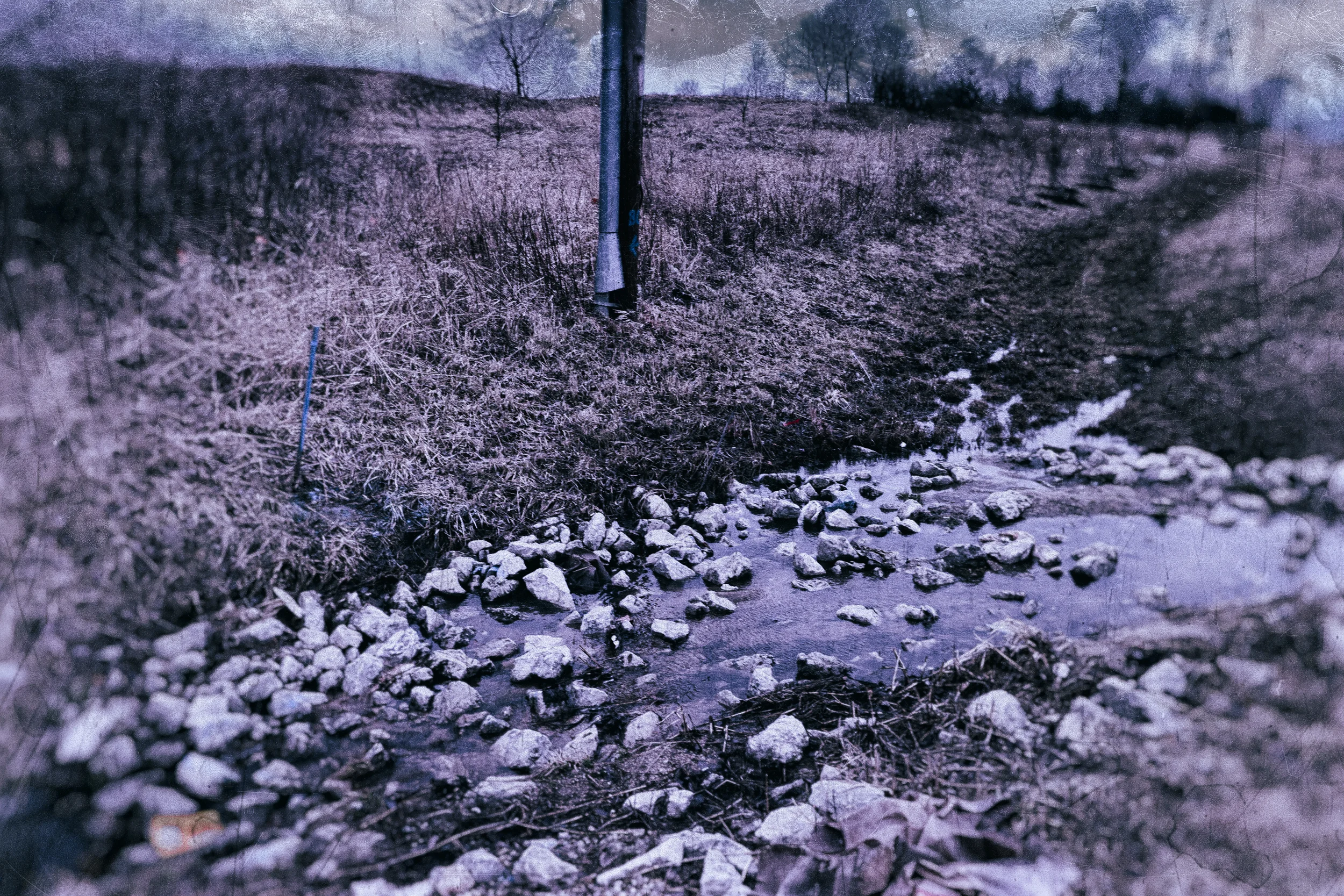

The Slaughterhouse is inspired by an excerpt from a short story written by Karen Halvorsen Schreck, my dear wife. Her inspiration came from a story her father told about a field trip his third grade class made to a slaughterhouse in Chicago in the 1920’s. It is hard to imagine taking children to such a brutal place, to witness such carnage, though it seemed to be common in the early 20th century. Karen fictionalized her father’s story; the protagonist became a little girl who decides to wear her white first communion dress the day her class made their visit.

When I read The Slaughterhouse, it felt like a harbinger of the violence that was to figure the 20th century: two world wars, genocides, ethnic and racial divides, environmental degradation, threats of nuclear warfare and nuclear accidents, the amassing of wealth by fewer and fewer… The list could be expanded. The world is at once more comfortable and more suffocating. The time preceding The Slaughterhouse marked the advent of industrialized killing that we all now depend upon. It pains me to point out that human life is as disposable as the animals.

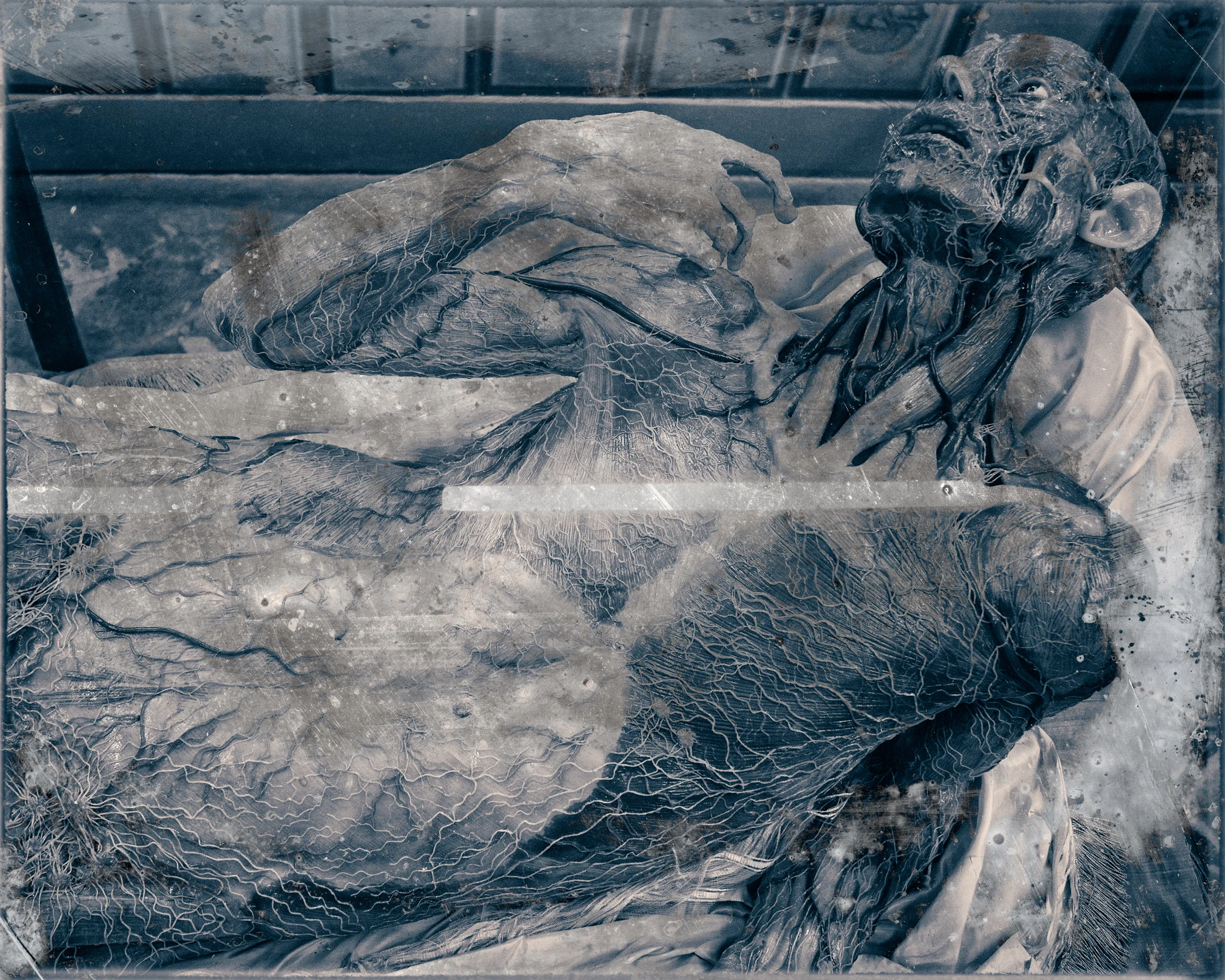

We almost didn’t visit Museo Zoologico La Specola, an eighteenth century natural history museum in Florence, the oldest in Europe. When we did, we were endlessly fascinated for an entire day. We walked through an endless labyrinth of rooms, each filled with glass cases containing specimens of every imaginable species: animals, insects, fish, birds, humans, reptiles, and fetuses… a dead Noah’s Ark. Some of the models date back to the Medici family. I thought they might provide a visual parallel, a poetic foil to push against The Slaughterhouse story.

There is only one Coliseum or Pantheon; but how many millions of potential negatives have they shed,—representatives of billions of pictures,—since they were erected! Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear; form is cheap and transportable. We have got the fruit of creation now, and need not trouble ourselves with the core. Every conceivable object of Nature and Art will soon scale off its surface for us. Men will hunt all curious, beautiful, grand objects, as they hunt the cattle in South America, for their skins, and leave the carcasses as of little worth.

The consequence of this will soon be such an enormous collection of forms that they will have to be classified and arranged in vast libraries, as books are now. The time will come when a man who wishes to see any object, natural or artificial, will go to the Imperial, National, or City Stereographic Library and call for its skin or form, as he would for a book at any common library. (1859)

-Oliver Wendell Holmes

Many pictures in the series are 16”x 20” and 20”x 24” metal prints with a shiny surface.

Full story at www.literal-latte.com/1995/05/the-slaughterhouse/

The Slaughterhouse is in process as a book.

The Slaughterhouse by Karen Halvorsen Schreck excerpt, a true story

The next morning, my grade school class was going to visit the slaughterhouse. I’d told Father, and he’d expressed some surprise, but then shrugged and said, “I suppose they know what’s good for you.” He was already at work when I got up, and Mother was out early as well, pushing you in your rickety wheelchair to the market. So the apartment was empty while I washed my face, ate my toast, and put on my new pink dress. It was as simple as that. It hung on me as simple as that. I looked in the mirror for a transformation, but didn’t find one.

Our class boarded a bus -this in itself an adventure, since most of us walked to school- and I sat down carefully in a seat near the front. The dress’s ruffles were already wrinkled, and my hands worked over the fabric, trying to press it into place. During the ride, I imagined all eyes on me, even the teacher’s, who lurched up and down the aisle, clutching at seats, swaying with turns, maintaining order with a swat of her hand. Her voice wove a net over our heads: “Stockyards . . . Packingtown . . . immigrants . . . millionaires and finest citizens . . . the future” -a vision that contained the vision I was having, of me rising like an angel, my hands raised in a blessing over my adoring classmates. “Look,” someone said. Clouds of thick, black smoke billowed before us. I recognized the smell. Or at least one layer of the smell. It was the odor of hot blood, flesh, and entrails, the odor of butchering I’d known that summer.

We filed out of the bus, and into the packinghouse, where we were greeted by a guide, an old, weary man who pulled balls of cotton from his ears when he said hello to our teacher, then immediately put them back in. Music floated through the entryway, a soothing melody, reasonable and decorous. “Mozart?” our teacher asked, but the man shrugged, pointing to his ears. When she gestured toward the radios lodged high in the four corners of the hall, he mouthed, “Oh,” and said, loudly, “To welcome visitors in. And to let the workers know when they’re back.”

He led us past a display of packaged meats, each piece labeled, its cut carefully printed on a card. We went outside and climbed a flight of stairs to a wooden catwalk, which overlooked the stockyards. The pens seemed to stretch on for infinity; at a certain point the animals grew indistinct from each other, and became a shifting mass. He pointed to a corral just beneath us, against the wall of the packinghouse. Inside it, a small group of cows stood in a circle, their noses touching, their breathing heavy, rhythmic. The wind carried the faint strains of the music we’d heard inside. Our teacher cleared her throat and reminded us about Orpheus, whose myth we’d studied earlier that winter. “See how music soothes the savage beast?” she said, then put her hand to her throat. “Or is it ‘breast?”‘ I tasted smoke and my tongue went chalky.

A herder moved around the cows, nudging their gleaming, brown haunches with his stick. Suddenly a door swung open, and he lunged at one of the herd, cursing as he prodded it toward the building. When it disappeared inside, the door swung closed.

“The chute,” the guide said. He sighed, turned away from the sight of the yards, and pushed his way through us. We followed him down the stairs, back into the building, through a set of metal swinging doors and out onto an observation platform.

At first, I couldn’t breathe. The place seemed to boil with something other than air, something more like soup, thickened with rot. Animals bellowed, men shouted, metal clanged and rattled. Hulking, lumbering shapes solidified into carcasses swaying, hanging suspended from chains. These bore great incisions, from which rose pockets of steam. Inside, membranes shimmered over organs. Men moved through this forest of meat, waving their arms like they were casting spells, wielding knives with blades like small scythes, blades like narrow daggers, blades broad as swords. They’d make passes over what dangled before them, sharpen their knives, then perform the same motions again on another, their magic practiced, precise and intricate. Their dull eyes never seemed to blink, set fast in slack faces, and glistening yellow pieces of fat and a bright sheen of blood covered their skin and clothes-covered everything. At the last stroke, hides dropped down into the muck with the weight of wet rugs, leaving behind naked gleaming flesh.

I looked away from all this, down at an empty pen. A man walked toward the door beside it, which he flung open. A steer entered, careening through the slime, and the man held up a hammer, its handle as long as an axe’s, its mallet a spike. He brought it down on the skull of the steer, the spike embedding there with a crack so loud, he might have been striking stone. The animal collapsed, shuddered, its broken head back, tongue slavering, the powerful muscles above its spine jerking. It rolled to the side as another animal entered, and it all happened again- only this steer had caught the scent of death, he reared and took a lunge that carried him half over the fence. The man cursed the steer’s mother, the children never to be sired, and landed a blow behind his ears. But this was not the right place. The animal took another leap forward, which tore his belly and left a jagged wound. Perhaps the cost of a hide so damaged would come out of the man’s pay- perhaps that’s why he went livid, veins thick as garden snakes pulsing in his neck, his spit budding at the corners of his mouth. He heaved the mallet high, then down with a groan, striking the animal between the shoulders. The steer pitched back, landed rolling in the blood and mud, and bellowed when the spike finally pierced his skull.

The man dropped his hammer on the ground and hunkered down, trying to catch his breath. He rested his head briefly on the broad, wet, shuddering flank of the steer.

“Children.” Our teacher’s voice trembled; it broke with something like laughter. “Let’s not lose our leader.”

We shuffled forward, toward the sound of the guide’s voice, shouting above the din, “We use everything but the squeal.” There was an abundance of squeals like screams. The man before us wore an apron furrowed with blood. He held a narrow knife. A pig spun by, upside down, glossy hooves flailing. One hind leg was hooked through a metal loop at the end of a chain. As it passed, the man darted forward and slit its throat. Blood black as oil gushed from the cut, pumping in bursts with the regularity of a heartbeat, hanging in arcs in the air.

Do you remember what Father read aloud from St. Augustine: when the blood runs out of an animal, the soul runs out too. I knew this meant that animals didn’t go to heaven, but what about the souls, running for eternity?

The man looked up and saw us watching him. Rows of children on a fieldtrip. He paused. Light gleamed on his slick skin. He pulled something from the deep pocket of his apron, waited for the next soft throat, slit it, and lifted what he held -a cup- up to the cut to catch the spurt of blood. He turned to us. “Time to go,” our teacher cried. I felt the press of bodies, smelled vomit, heard sobs and laughter. Then the man looked right at me-at the girl holding herself just so in her child star’s dress-raised the cup in a toast, and drank.

Why is everyone breathing so loudly, I wondered. People, speaking too slowly, are fading away. We must be leaving; I am ready to leave as well.

But Sophy, in the next moment, I saw you there instead of the pig, caught up by one small foot, your hair and arms hanging down and swinging as gently as the tumbled ruffles of your pink dress, as gently as a pendulum; and I stood beside you, instead of the man, holding high a glass of Cherry herring. I put it to my lips and drank until the sticky red stuff ran down my chin.

Was there a knife in my hand, was there a wound at your throat, would I be haunted by your soul? Finally home, I ran to my room, and shed the mess I wore, the dress falling to the floor like a rotting flower. Mother and Father were in the kitchen, shouting- their two languages skidding in and out of each other, a blur of voices translating money and ruin, the cost of a baptism dress. I found you on your bed, the muscles in your face still and beautiful in repose. I thought you were dead, and threw my body down beside you. But you opened your eyes and grinned, then frowned, garbling words you surely understood, your hands batting the air. I grabbed your arms and put them around my neck, and with a strength that jarred my breath, you pulled me to you, nestling my head beneath your chin. As if you’d been waiting, you held me there, kissing the place where a spike shatters the skull of a slaughtered calf.

The Slaughterhouse by Karen Halvorsen Schreck, an excerpt

The next morning, my grade school class was going to visit the slaughterhouse. I’d told Father, and he’d expressed some surprise, but then shrugged and said, “I suppose they know what’s good for you.” He was already at work when I got up, and Mother was out early as well, pushing you in your rickety wheelchair to the market. So the apartment was empty while I washed my face, ate my toast, and put on my new pink dress. It was as simple as that. It hung on me as simple as that. I looked in the mirror for a transformation, but didn’t find one.

Our class boarded a bus -this in itself an adventure, since most of us walked to school- and I sat down carefully in a seat near the front. The dress’s ruffles were already wrinkled, and my hands worked over the fabric, trying to press it into place. During the ride, I imagined all eyes on me, even the teacher’s, who lurched up and down the aisle, clutching at seats, swaying with turns, maintaining order with a swat of her hand. Her voice wove a net over our heads: “Stockyards . . . Packingtown . . . immigrants . . . millionaires and finest citizens . . . the future” -a vision that contained the vision I was having, of me rising like an angel, my hands raised in a blessing over my adoring classmates. “Look,” someone said. Clouds of thick, black smoke billowed before us. I recognized the smell. Or at least one layer of the smell. It was the odor of hot blood, flesh, and entrails, the odor of butchering I’d known that summer.

We filed out of the bus, and into the packinghouse, where we were greeted by a guide, an old, weary man who pulled balls of cotton from his ears when he said hello to our teacher, then immediately put them back in. Music floated through the entryway, a soothing melody, reasonable and decorous. “Mozart?” our teacher asked, but the man shrugged, pointing to his ears. When she gestured toward the radios lodged high in the four corners of the hall, he mouthed, “Oh,” and said, loudly, “To welcome visitors in. And to let the workers know when they’re back.”

He led us past a display of packaged meats, each piece labeled, its cut carefully printed on a card. We went outside and climbed a flight of stairs to a wooden catwalk, which overlooked the stockyards. The pens seemed to stretch on for infinity; at a certain point the animals grew indistinct from each other, and became a shifting mass. He pointed to a corral just beneath us, against the wall of the packinghouse. Inside it, a small group of cows stood in a circle, their noses touching, their breathing heavy, rhythmic. The wind carried the faint strains of the music we’d heard inside. Our teacher cleared her throat and reminded us about Orpheus, whose myth we’d studied earlier that winter. “See how music soothes the savage beast?” she said, then put her hand to her throat. “Or is it ‘breast?”‘ I tasted smoke and my tongue went chalky.

A herder moved around the cows, nudging their gleaming, brown haunches with his stick. Suddenly a door swung open, and he lunged at one of the herd, cursing as he prodded it toward the building. When it disappeared inside, the door swung closed.

“The chute,” the guide said. He sighed, turned away from the sight of the yards, and pushed his way through us. We followed him down the stairs, back into the building, through a set of metal swinging doors and out onto an observation platform.

At first, I couldn’t breathe. The place seemed to boil with something other than air, something more like soup, thickened with rot. Animals bellowed, men shouted, metal clanged and rattled. Hulking, lumbering shapes solidified into carcasses swaying, hanging suspended from chains. These bore great incisions, from which rose pockets of steam. Inside, membranes shimmered over organs. Men moved through this forest of meat, waving their arms like they were casting spells, wielding knives with blades like small scythes, blades like narrow daggers, blades broad as swords. They’d make passes over what dangled before them, sharpen their knives, then perform the same motions again on another, their magic practiced, precise and intricate. Their dull eyes never seemed to blink, set fast in slack faces, and glistening yellow pieces of fat and a bright sheen of blood covered their skin and clothes-covered everything. At the last stroke, hides dropped down into the muck with the weight of wet rugs, leaving behind naked gleaming flesh.

I looked away from all this, down at an empty pen. A man walked toward the door beside it, which he flung open. A steer entered, careening through the slime, and the man held up a hammer, its handle as long as an axe’s, its mallet a spike. He brought it down on the skull of the steer, the spike embedding there with a crack so loud, he might have been striking stone. The animal collapsed, shuddered, its broken head back, tongue slavering, the powerful muscles above its spine jerking. It rolled to the side as another animal entered, and it all happened again- only this steer had caught the scent of death, he reared and took a lunge that carried him half over the fence. The man cursed the steer’s mother, the children never to be sired, and landed a blow behind his ears. But this was not the right place. The animal took another leap forward, which tore his belly and left a jagged wound. Perhaps the cost of a hide so damaged would come out of the man’s pay- perhaps that’s why he went livid, veins thick as garden snakes pulsing in his neck, his spit budding at the corners of his mouth. He heaved the mallet high, then down with a groan, striking the animal between the shoulders. The steer pitched back, landed rolling in the blood and mud, and bellowed when the spike finally pierced his skull.

The man dropped his hammer on the ground and hunkered down, trying to catch his breath. He rested his head briefly on the broad, wet, shuddering flank of the steer.

“Children.” Our teacher’s voice trembled; it broke with something like laughter. “Let’s not lose our leader.”

We shuffled forward, toward the sound of the guide’s voice, shouting above the din, “We use everything but the squeal.” There was an abundance of squeals like screams. The man before us wore an apron furrowed with blood. He held a narrow knife. A pig spun by, upside down, glossy hooves flailing. One hind leg was hooked through a metal loop at the end of a chain. As it passed, the man darted forward and slit its throat. Blood black as oil gushed from the cut, pumping in bursts with the regularity of a heartbeat, hanging in arcs in the air.

Do you remember what Father read aloud from St. Augustine: when the blood runs out of an animal, the soul runs out too. I knew this meant that animals didn’t go to heaven, but what about the souls, running for eternity?

The man looked up and saw us watching him. Rows of children on a fieldtrip. He paused. Light gleamed on his slick skin. He pulled something from the deep pocket of his apron, waited for the next soft throat, slit it, and lifted what he held -a cup- up to the cut to catch the spurt of blood. He turned to us. “Time to go,” our teacher cried. I felt the press of bodies, smelled vomit, heard sobs and laughter. Then the man looked right at me-at the girl holding herself just so in her child star’s dress-raised the cup in a toast, and drank.

Why is everyone breathing so loudly, I wondered. People, speaking too slowly, are fading away. We must be leaving; I am ready to leave as well.

But Sophy, in the next moment, I saw you there instead of the pig, caught up by one small foot, your hair and arms hanging down and swinging as gently as the tumbled ruffles of your pink dress, as gently as a pendulum; and I stood beside you, instead of the man, holding high a glass of Cherry herring. I put it to my lips and drank until the sticky red stuff ran down my chin.

Was there a knife in my hand, was there a wound at your throat, would I be haunted by your soul? Finally home, I ran to my room, and shed the mess I wore, the dress falling to the floor like a rotting flower. Mother and Father were in the kitchen, shouting- their two languages skidding in and out of each other, a blur of voices translating money and ruin, the cost of a baptism dress. I found you on your bed, the muscles in your face still and beautiful in repose. I thought you were dead, and threw my body down beside you. But you opened your eyes and grinned, then frowned, garbling words you surely understood, your hands batting the air. I grabbed your arms and put them around my neck, and with a strength that jarred my breath, you pulled me to you, nestling my head beneath your chin. As if you’d been waiting, you held me there, kissing the place where a spike shatters the skull of a slaughtered calf.